Electronic english version since 2022 |

The newspaper was founded in November 1957

| |

|

Number 7-8 (4655-4656) The special report dedicated to the 110th anniversary of Academician G.N.Flerov: |

The special report dedicated to the 110th anniversary of Academician G.N.Flerov

"In science it is very important to go your own way"

The original phrase of Academician Georgy Nikolaevich Flerov, with which I have titled my memoirs-notes, has remained in the brochure "These omnipresent ions" and I will return to its history later. In my opinion, it very accurately characterizes Flerov as a scientist and his personality, even the very construction of the phrase, if you break away from its content. "In science" is not only a circumstance of place answering the question "where?" It is the main content of his life. "Very important" is not just an adverb with emphasis. It is the way of his actions, focusing on the essential, rejecting the secondary. The verb form "to go" agrees with the possessive pronoun and the subject according to all the rules, but it is emphasized: "your own". Of the many phrases of Georgy Nikolaevich, said and written down by me on various occasions this is the one that has stuck in my memory...

The original phrase of Academician Georgy Nikolaevich Flerov, with which I have titled my memoirs-notes, has remained in the brochure "These omnipresent ions" and I will return to its history later. In my opinion, it very accurately characterizes Flerov as a scientist and his personality, even the very construction of the phrase, if you break away from its content. "In science" is not only a circumstance of place answering the question "where?" It is the main content of his life. "Very important" is not just an adverb with emphasis. It is the way of his actions, focusing on the essential, rejecting the secondary. The verb form "to go" agrees with the possessive pronoun and the subject according to all the rules, but it is emphasized: "your own". Of the many phrases of Georgy Nikolaevich, said and written down by me on various occasions this is the one that has stuck in my memory...

Today marks the 110th anniversary of the birth of the outstanding Russian scientist Academician Georgy Nikolaevich Flerov, founder of the Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions that bears his name.

One day of Georgy Nikolaevich or Polyvalent Flerov

Back in 1983, materials for the 70th anniversary of the birth of Academician Georgy Nikolaevich Flerov were prepared for the weekly "Dubna" in advance and the editor Svetlana Kabanova suggested: "Molchanov, why don't you make an author's material about the Academician? Describe just one of his working days and show how much it contains."

I must say that there have never been such precedents in our Institute newspaper, for which I have worked as a correspondent for more than a dozen years, as for such anniversaries, special articles were usually prepared under high signatures in the journal "Advances in Physical Sciences" and duplicated in the newspaper. For example, in our editorial office there is a large portrait of Mikhail Grigorievich Meshcheryakov hanging on the wall. The table in front of him is covered with flowers and the bottleneck of a still uncorked bottle of cognac peeks out from behind them. In the hands of one of the founding fathers of Dubna is our newspaper that he reads attentively. The newspaper, I think, is open just at the article about the anniversary that the hero of the day certainly had a hand in writing. Who else would be entrusted with such an important task? But G.N. was exactly the figure that attracted journalists to him and unlike some other figures of similar celebrity (that were quite private), he encouraged such cooperation. The editor was very well aware of this.

Vladimir Borisovich Kutner, a great friend of our newspaper, my countryman and also a graduate of the second school on the right bank of the Volga, an interested and sympathetic person told the Director of the Laboratory about this idea of the editorial office. G.N. accepted our idea (to describe his working day) as good, one might even say with tacit approval and on a day in February, 1983, I became his shadow. I was even honoured with an invitation to lunch - when else could I have a tasteful talk? G.N. also invited the director of the plant on the Cheleken Peninsula to dinner, who he had common interests with. Cheleken was marked on maps as one of the search points for superheavy elements in nature.

We were sitting at a table by a large window overlooking the Volga embankment and the park, wrapped in February snowdrifts. "Well, how is our Academician?" the editor asked me in the next morning. "When did your working day end?" he asked. "About nine o'clock in the evening," I said. "It was inconvenient to stay any longer. And I guessed that he got tired of me, too." "Lest you get bored further, sit down and write!"

So, I started to write. And... I wrote what we collectively dubbed the "time clerk's diary" - it was a protocol-accurate time-study of the working day interspersed with dialogues and a list of meetings, conferences and others. By the way, having re-read this "diary", extracted from the archive of those years, I still found some fragments there that were not included in the human-interest story, but are quite interesting today, a quarter of a century later... In our genre definition of the first version of the text as a time clerk's diary, there was a certain reality of those times, anticipating a short period of Andropov's tightening of the screws: G.N. decided to streamline the flow of laboratory life and ordered a composter and time cards to be swiped in the lobby that employees had to punch in order to keep track of working hours. As it often happened, he started with himself and famously punched through any piece of paper, if he did not catch the eye of a time card. This is, so to say, laboratory folklore that in no way detracts from the importance and role of the director in the eyes of the employees. On the contrary, it "insulated" his image.

Something similar had been invented for him even earlier by the shift supervisors of the accelerator on the control panel. Knowing his passion for leading by example and fearing the failure of the painstaking adjustment of the acceleration mode, they had somewhat reconstructed the control system. G.N. had a favourite knob on the control panel that he often twiddled and in his excitement, knocked over the parameters carefully maintained by the operators. Eventually, they disconnected all the wiring from the knob. And then, the "knob of GeeNa" had no effect on anything. He still came to the control room, followed the readings of the instruments, asked the operators and began to turn "his knob". Then he would look at the staff on duty triumphantly: "Well, now that's good"...

So, the editor and I had a long discussion about how to write this article. The editorial "kitchen" then included, in addition to typewriters, paper, scissors and glue, also brains as seasoning. And it was decided to completely revise my "time-study", enhancing its journalistic sounding. It was said and done. Flerov accepted the final version of the text from the first submission. Later, I became convinced as a co-author of the scientist, it did not happen often.

On 2 March, on the day of the anniversary of the Academician, my exclusive was published in our newspaper and its abbreviated version - in "Komsomolskaya Pravda". True, in the central youth newspaper, the headline "Polyvalent Flerov" was changed to "One day of Director", without agreeing with me but nothing could be done, as each body has its own costs...

...By the end of the very day that I had the role of becoming the shadow of the scientist, I was like a squeezed orange and 70-year-old Georgy Nikolaevich was fresh as a daisy. When I was about to leave, he took out reprints of fresh articles from this director's briefcase and intended to work some more. And in the early morning, as usual, one of his employees was woken up by a phone call: "Don't you think that the target is rather weak, because we are about to increase the intensity of the beam?"

The main thing in a scientist's life is pace, I wrote, inspired by communication and trying to convey to an unruly sheet of paper the charm of Georgy Nikolaevich's personality. Pace and a sense of time. Flerov's career started in the first year of the first five-year plan. "Time, forward!" - this motto determined the atmosphere in which the character of the future scientist was developed.

They told about young Flerov that when I.V.Kurchatov took him as a trainee, he acquired a successor in the "sprinting": the new employee raced along the Institute corridors with such a passion that everyone literally shied away from him. Sport always had an important role in Georgy Nikolaevich's life. So, on that memorable day for me, he said, slightly paraphrasing Goethe's famous phrase: "Only the one is worthy of life and health that every day goes to fight for them." With these words, he slowly went down into the water, swam four laps in alternating breaststroke, also his favorite folk style "on the side" and did exercises. After that, he came up to the coach's table, on which there was a telephone and dialed the number:

"Do you know what I have come up with? How about lavsan fifty microns thick? Let's see what it would do...

The phone conversation went on for a few minutes. The working day started for someone of the staff, too.

While preparing a book about the scientist later for publication, I met with Georgy Nikolaevich's son in his Moscow flat, where I had been the last time G.N. had endorsed the manuscript of our brochure "These omnipresent ions." Nikolay Georgievich gave me some materials from his father's archive - postcards, photographs, manuscripts, newspapers and an interview with an English TV correspondent and a German journalist Heinemann. Hearing a familiar voice on the phonograms, I felt as if I was transported back to those times when we had met in Flerov's cottage in Dubna to work on the manuscript ... But let's leave our emotions. Having deciphered the phonograms, I found fragments that as if summed up this versatile and vivid life and I decided to bring them here without changing anything: as it is said, so it is said and most importantly, to be heard.

|

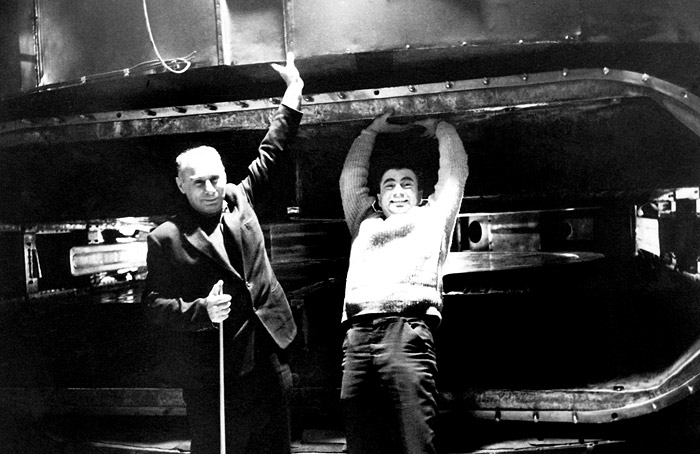

| I.V.Kurchatov and G.N.Flerov, 1950s |

The versatility of the Laboratory Director's interests struck the imagination of many. In the book "On the way to superelements" that he wrote together with his colleague PhD in Physics and Mathematics A.S.Ilinov for the "Children's Encyclopedia Library", issued by the publishing house "Kvant", the places where samples were taken to search for superheavy elements were shown on the map of the globe. Meteorites, ores, minerals, volcanic lava, geothermal water, ferromanganese nodules from all over the world - only the ice continent of Antarctica, it seems, was not "attacked" by FLNR physicists that were sent by G.N.Flerov on an expedition to search for superheavy elements in natural samples.

Equally wide was the scope of the "seed fields" - about 90 organizations in the country used the results of FLNR nuclear physics research in practice. This was also the subject of the morning meeting that was attended by the staff members of the Department of Applied Nuclear Physics. Next to Georgy Nikolaevich, one could feel time shrinking and compacting, because the deeds of dozens of people that he guided eventually spread to thousands of people and deeds. "Abstract" scientific discoveries, in Flerov's deep conviction, always entail a range of important practical applications. On that day, next to G.N., for the first time, I understood that much of what he did had begun long ago...

...In Kazan, more than half of the Academy was evacuated. Everyone was hungry and cold, nothing could be done and there we had some fantasies. Therefore, the attitude was also cold, especially bearing in mind that Kurchatov at that moment in Sevastopol was engaged in mines. And therefore, I single-handedly persuaded: leave what you consider very important today and get busy finding out what kind of bomb it should be in order at least to prevent the Germans from making this bomb. After the report, I first personally talked to Ioffe and then to Kapitsa, he told me: "You are now alone and together with Kurchatov you are a great force. Write him a letter." I wrote this letter, outlining my thoughts, why and what should be done. Well, even then, in that situation, somehow fantasizing ... There was a design of this very ... atomic bomb that generally coincided with what the Americans used in Hiroshima.

In research paper, in general, like in chess, one move should be followed by the next and then the next one - the logic must be the same. I was convinced of this in Washington when we like others, made reports on what had been done in each country for the development of an atomic bomb and we found out that we did the same...

"What is the budget of your plant?" the question of the Academician seemed to catch another guest-practitioner, Director of the plant on the Cheleken Peninsula, where the FLNR facilities for the geothermal water analysis were located, by surprise. "We, too, until recently, have pulled more from the state. But with the implementation of nuclear filters into production, the situation began to change."

"Unfortunately, Dubna is a mono-science city," he said a little later, distracted from immediate affairs, papers, orders. "Other scientific centres, such as Protvino, Pushchino suffer from the same. And today, this one-sidedness starts to affect us in a certain way. It is no coincidence that very interesting work is carried out in Novosibirsk, at those points of science growth that are on the borders of many areas of knowledge. Today, I feel the tasks that produce results should be based on many achievements. It is very good that geologists, biologists and geochemists visit us. And science is respected in mining pits, mines, opencasts, geological parties and our employees go to practitioners themselves, consult with them and show them the advantages of new techniques. After all, practitioners sometimes need to be forced to turn to something new that appears in nuclear physics with approximate intervals of two years.

Reporter's voice: How did you imagine in 1945 how long it would take you to get a controlled fission reaction?

Flerov's voice: Everyone in his own way. But Kurchatov behaved as if he really knew everything, that everything would work out and it would work out quickly. Although in fact, he doubted, of course, more than we did. But he understood that the director's doubt would affect the work of his subordinates. Although everything, everything, in general, was hanging by a thread. But I told you that geologists had found a sufficient amount of uranium only in 1945. Little was obtained from Germany, not much from Czechoslovakia. Soviet uranium was obtained just in 1945 when batches were sent, when dosimeters were given to the military and schoolchildren, when science was involved: look for it and then you will explain. Indeed, they found it...

Since 1945, after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we have made great strides. If (for the project - E.M.) at first, one hundred people were recalled, later, there were thousands, tens of thousands and it was very reasonable that Kurchatov did not encourage anyone to come here, but set tasks in their institutes and those who worked better, only then he took to him. If I say that by the end of the Atomic Bomb Project there were already hundreds of thousands of people (involved in it - E.M.), I think that it was like this. To some extent, related to the overall problem.

During the day, in his study, in the corridors of the laboratory, in the rooms of physicists, the director suggested a lot of ideas, gave addresses where one could ask for help or conversely, where one could help. The very geography that united the laboratory with many parts of the world by dozens of threads "worked". The very experience that came to one of Kurchatov's assistants during the "nuclear assault" years "worked".

G.N.Flerov and Yu.Ts.Oganessian. Dubna, 1965

At the methodological seminar, Georgy Nikolaevich asked each speaker a question: what of whatever has been done is important for application in related areas of science, in practice? And he also spoke at the seminar:

"We should be very keen today to raise the issue of the integrity of the scientist, to increase his impact. Recently, the State Committee for Science and Technology has taken control of several discoveries of significant practical importance. It has turned out that either they have been not implemented, or the process has been so slow that over time, there has been no need for this work. I don't know about you, but I have asked myself: what have I done? I think we should carry out further research that we currently do and try to bring the results to practical use.

A little earlier, answering other questions: why are you always embraced by new plans, new ideas? Don't you feel like taking a break or engaging in quieter activities? - G.N. wrote in the book on superelements: "I think there is a simple advice that will help to find the answer to such questions. You need to take a moment, to look at your work from the outside and think about whether there is much left to be done compared to what has already been done. If there is less or about the same, then perhaps it is worth looking for something else to do."

Everything was clear here. Only one thing was not clear: when did Georgy Nikolaevich find a free moment to stop and look around...

Reporter's voice: Were you at the first Soviet test? Can you describe it and the preparation for it?

Flerov: There won't be enough tape. I was. And since there was my detector, I was watching to see if there would be a deviation from the design value. So, of course, I was there. I was the last to go down the tower. And then, together with Kurchatov, I was in the casemate. And when the explosion had already happened, Kurchatov at that moment, apparently, took this terrible tension out of his mind: whether it would go off or not. Ten percent was in favour of the failure. He jumped out of the casemate and shouted: "I've got it! I've got it!" Such words. However, a cloud of dust went down on the casemate, I was also in a state of excitement, although approximately, the coefficient was zero, seven from Kurchatovsky, but nevertheless, I grabbed him in an armful and dragged him into the casemate. That's how it all was. That's what is remembered.

The word "pace", so popular in the 1930s, I ended my story about one day of the director, defines the rapid rhythm of modern nuclear physics and the winged "Time, go!" hovers over every working day. On an ordinary day, no champagne bottles are smashed against the magnet of the new accelerator, there are no exclamations of "Eureka" and no State Prizes are awarded ...

G.N.Flerov, Yu.Ts.Oganessian, G.Seaborg (USA). Dubna, 1969

In the Laboratory that bears his name, the bright image of the teacher has been preserved in the memory of many. Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences Yuri Tsolakovich Oganessian, successor to Georgy Nikolaevich, characterizes the first director as follows: "An outstanding personality, a physicist from God, a convinced, passionate, resolute, purposeful person, possessing fantastic scientific intuition and having a gift to fascinate many of the scientists brought up by him with his ideas, he founded a new scientific area - heavy ion physics... The personality of this man largely determined the scientific face and the research style of the laboratory."

He was an ardent patriot of Dubna and although he perfectly knew all the downsides concerning the "one-sided" development of the centre of monoscience and never declared his love for these places, in which he found himself at the behest of his supervisor I.V.Kurchatov, the huge baggage that G.N. left to his successors, will serve for many more years. Just as for many years and epochs, one of the new elements, discovered at JINR under his supervision and named Dubnium, has firmly taken its place in the Periodic Table of Elements.

The materials of the special issue prepared by Evgeny MOLCHANOV,

Illustrations from the JINR photo archive